How Sarasota Artist Gil Elvgren Helped Define the Pin-Up Aesthetic

Flirtatious, revealing images of beautiful, idealized women, either in photographs or illustrations, became wildly popular among American troops who were stationed far from home during World War II. Soldiers would post the alluring pictures on their lockers as an escape from their often-terrifying circumstances, leading to the nickname bestowed upon the genre—the pin-up—and the women depicted in them: pin-up girls.

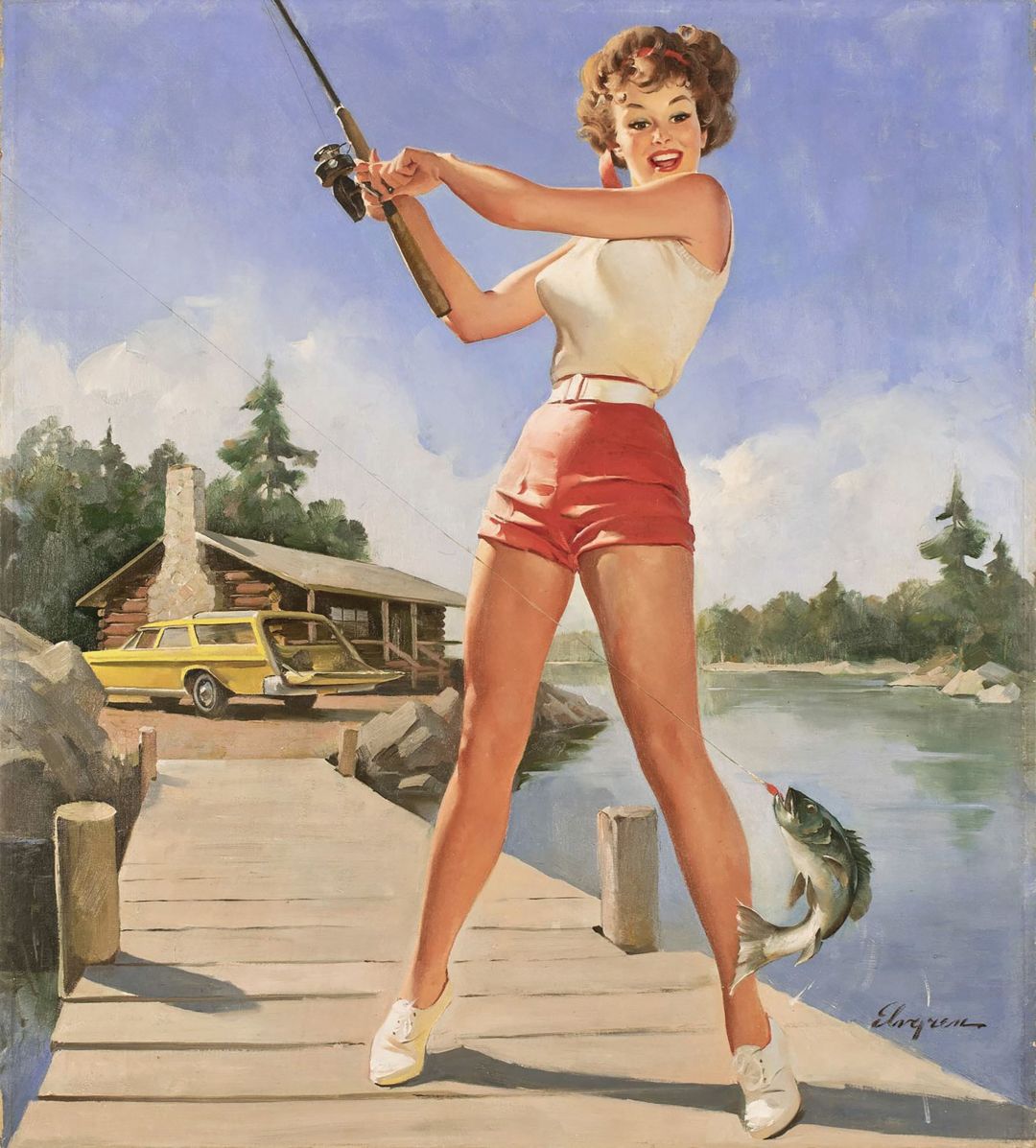

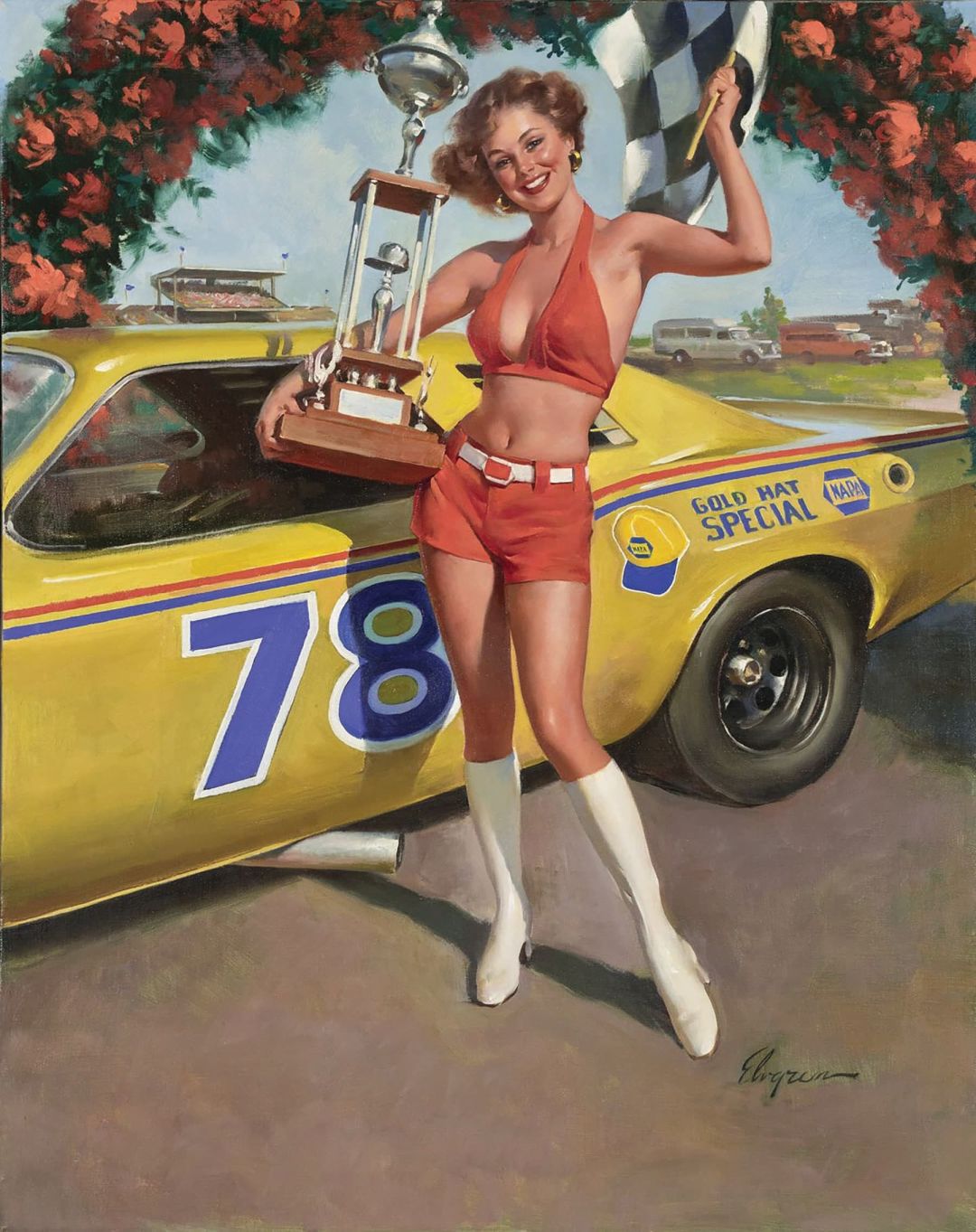

For decades after the end of the war, these images were a fixture of calendars, postcards, billboards and magazines—and many of them were crafted in Sarasota. Between the mid-1930s and the early 1970s, artist Gil Elvgren produced more than 500 pin-up paintings that appeared in ads and publications nationwide, making him one of Sarasota’s most popular and widely viewed artists. Fans of the pin-up genre say his work towers above that of his rivals, in part because he preferred to work with oil on canvas, a laborious technique that set his images apart from those of peers like Alberto Vargas and George Petty. “A lot of the pin-up artists worked in pastels,” says Louis Meisel, one of New York’s best-known gallery owners and a co-author of Gil Elvgren: The Complete Pin-Ups, the definitive book on the subject. “It was a lot quicker and easier. They weren’t planning on showing them in galleries or framing them. But you never get the kind of detail and beauty that you do with an oil painting.” Meisel views Elvgren as the genre’s top artist, arguing that Elvgren’s competitors lacked his technical skill and that their work had none of Elvgren’s images’ distinct personality. “Elvgren did beautiful paintings on canvas,” Meisel says. “They’re humorous. They’re sexy but chaste.”

Gillette Alexander Elvgren was born on March 15, 1914, in St. Paul, Minnesota. He originally wanted to become an architect, but after graduating from University High School, he decided to attend the Minneapolis Institute of Art. He moved to Chicago, completed his artistic training at the American Academy of Art, and along the way married his high school sweetheart, Janet Cummins.

“My mom was little. She was about 4 feet 11 inches, adorably cute,” says Drake Elvgren, one of Gil and Janet’s two sons. “I think that’s why Dad fell in love with her. He always liked cute girls, not the raving beauties.”

In Chicago, Elvgren moved toward realistic painting after coming across the work of fellow American Academy of Art alum Haddon Sundblom, best known for the images of Santa Claus he created for Coca-Cola. Sundblom painted pin-ups, as well.

Initially, Elvgren earned a living painting for the advertising agency Stevens/Gross, but after a year with the firm, he moved on to Louis F. Dow, which published calendars and a wide range of other printed materials. It was there that Elvgren started painting large numbers of pretty girls and completed illustrations for the top magazines of the day: McCall’s, Collier’s and the Saturday Evening Post. Elvgren painted dreamy, buxom and approachable young women, juxtaposing a lush palette of colors with friendly faces, and provocative physicality with playful poses, red lips and rosy cheeks. He depicted women as both naughty and nice, transfixing millions who gazed at them.

In addition to his magazine work, Elvgren painted for a bevy of top American corporations—Ford, Studebaker, Coca-Cola, General Electric, Schlitz, Crush and General Tire, to name a few—and his work even appeared on the noses of military bombers pummeling the Axis powers during World War II. In 1944, Elvgren started painting pin-ups for Brown & Bigelow, then the country’s leading publisher of calendars, and over the next few decades, he produced many of his most popular works. His talent was in high demand.

“Dad painted from black and white photos,” says Drake. “He would take 24 pictures and say, ‘Gee, I like the left arm angle on this one,’ and cut it out and paste it on.” Much later, Drake published a book that juxtaposed his father’s paintings with the original black and white photographs that he took of his models. Elvgren liked to work from black and white because “he didn’t want to be influenced by color,” Drake says. “He would use the same model for several different paintings, and he wanted to be able to change the color of her hair and not be influenced by the color of her dress.” Actresses Donna Reed and Kim Novak were among the women who modeled for Elvgren when he was working in Chicago. He told one interviewer that “a gal with highly mobile facial features capable of a wide range of expressions is the real jewel. The face is the personality.”

A 1962 profile in the St. Petersburg Times described Elvgren as the artist who “draws those curvy calendar girls that your husband insists on hanging up in the garage or his den.” Elvgren told the newspaper that he intentionally shied away from trendy looks, preferring timeless details. “I can’t follow any specific style trend,” he said. “If I were to put some silly beehive hairdo or high-style shoes on a girl, the vogue might be out of date when the calendar is published.”

“I try to get a girl caught at some inopportune moment which will immediately pass away. It gives the picture a naturalness,” he went on. “The old method of posing a model for hours at a time is gone.”

Image: Courtesy Drake Elvgren

By 1956, Elvgren was at the height of his powers as a painter, and he and Janet, along with daughter Karen and sons Gillette Jr. and Drake, picked up and moved to Siesta Key, where they bought three acres of land. Drake was 12 years old at the time. He and his brother attended Brookside Junior High and Riverview High School. Drake, now 80, still lives in the area.

“For a kid, living a quarter mile from the beach was especially nice,” says Drake. “I could walk 30 feet from the back door and be in the boat and go off water skiing.” On Siesta Key, Elvgren indulged his passion for architecture by designing his own home alongside legendary architect Victor Lundy. The Elvgrens’ four-bedroom, 3,500-square-foot abode had a screened-in porch that looked out onto Sarasota Bay.

“There wasn’t a supporting wall in the house,” says Drake. “It was all post and beam, and all the interior walls were tongue and groove cypress. Dad wanted to have a house with a studio, so when he built the house, he built a 20-by-20 studio over the carport.”

Elvgren and his family found plenty of ways to enjoy their free time in Sarasota. Janet was a spectacular host of cocktail and dinner parties, known for her joviality and kindness. She was also a talented clothing maker and cook, and a devout Christian who attended services at St. Boniface Episcopal Church on the key. “She was a very loving mother,” says Drake.

The family lived near Siesta Key’s south bridge, close to the home of novelist John D. MacDonald, one of the most popular writers of his generation. Best known for his Travis McGee series and the 1957 novel The Executioners, which was adapted into the 1962 film Cape Fear and its 1991 remake, MacDonald would play chess with Elvgren on Wednesdays. Elvgren made many other friends in Sarasota’s artistic community—people like Andersonville author MacKinlay Kantor, painter and illustrator Ben Stahl, comic strip artist V. T. Hamlin, and Tom T. Chamales, the author of Never so Few, which became a 1959 film starring Frank Sinatra, Steve McQueen and Gina Lollobrigida. Elvgren loved taking his boat to restaurants, where he played liar’s poker, in which players wagered on the serial numbers of a dollar bill. He collected firearms and won statewide target shooting competitions. “He’d shoot a .45 pistol at 50 yards and put 10 shots in a row in a two-inch circle,” says Drake. Elvgren also loved fast cars and drove a fire-engine-red Jaguar XK120 and a Mercedes-Benz 190SL.

But finding models for Elvgren’s paintings proved difficult in Florida. When he lived in Chicago, a large milieu of models coalesced around the American Academy of Art. In Florida, the process was more hit or miss. On one occasion, Elvgren was searching for a model for an upcoming National Automotive Parts Association calendar, and Drake discovered one while partying at a go-go dance club. “I saw her and thought Dad would like her,” says Drake. “He went out there the next night, and the next NAPA calendar was her. He even painted her Camaro into it.”

Image: Louis K. Meisel Gallery

The Elvgrens’ blissful Siesta Key world was shaken when Janet was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in the mid-1960s. She died in 1966 at age 51. “Dad changed dramatically after Mom died. She was so young,” Drake says. In the years after Janet’s death, Elvgren’s work suffered, according to Drake. “His backgrounds got less detailed,” he says.

During the ’70s, however, the quality of Elvgren’s paintings began to improve, thanks in large part to a new muse who served as a model for several of his paintings. She was well into her 40s and proved that Elvgren could depict middle-aged women as well as young beauties.

But as photography became more widespread in advertising and publishing, the demand for illustrated pin-ups declined. “At one point later in life my dad said, ‘Maybe I sold myself short with the pin-ups,’” Drake says. “As he was getting older, he saw that the pin-up business was going away.” Drake, who has represented his father at awards ceremonies and other events, says his advice to young artists is to not become tied down to one specific genre. “That limits you,” he says. At one point, Drake encouraged Elvgren to join him and his wife in Houston and try his hand at portraiture, but Elvgren didn’t want to leave Sarasota. “He just adored Sarasota,” says Drake.

Over the course of the 1970s, Elvgren’s production slowed, and, like Janet, he became deeply religious. He died of cancer on Feb. 29, 1980, two weeks shy of his 66th birthday, leaving behind a complex legacy. On one hand, Elvgren’s work has left a lasting imprint on pop culture that can be seen in everything from the look of fashion photography in Vogue and Esquire in the 1970s to MTV’s “video vixens” in the 1980s to Instagram models and burlesque performers today. His work is still at home in Sarasota, too, where prints of his images can be found in vintage shops and on the walls of establishments like Owen’s Fish Camp. (In 2010, an homage to an Elvgren image was created as part of that year's Chalk Festival.) But conservative observers sometimes view his work as risqué and argue that it commodifies the female form, while feminists have argued that Elvgren’s images objectify women and uphold unattainable beauty standards. The recent push for more realistic-looking models in advertising can, in part, be seen as a response to an aesthetic that Elvgren helped cultivate.

Drake says his father didn’t like art critics. “Professors love to tell you, ‘Well, the artist was thinking this when he did this,’” says Drake. “They tried to do that with Dad a couple times and he’d say, ‘That’s stupid. I did that painting because I needed the money.’”

In Elvgren’s later years, however, his reputation as a great American artist began to develop, thanks in large part to Meisel, who situates his work in the long tradition of realism in American painting. Meisel started buying Elvgren’s paintings in the early 1970s, acquiring his canvases for as little as $300. In many cases, the original paintings were given to customers who had ordered large numbers of pin-up calendars and sat in storage for years before Meisel tracked them down. Today, original Elvgren paintings go for as much as $250,000, and Meisel has shown nearly 300 of them in his gallery.

“The critics kind of laughed at me, and no museum wanted them,” says Meisel. “They’d say, ‘Oh, these are just illustrations.’” Despite the popularity of Elvgren’s paintings, museums and galleries are hesitant to host exhibitions of his work, although his work was included in a 2004 show at Ringling College of Art and Design.

“There was never anything obscene or dirty about his work,” says Drake. “It was a cute girl next door showing some legs, showing some cleavage occasionally. He was so good at it.”