Content warning: this page contains videos and written descriptions detailing violent attacks against protesters. We are publishing this material to evidence human rights violations.

executive summary

Mozambicans have taken to the streets to protest contested election results and other socioeconomic and political grievances. Instead of protecting their rights to peaceful assembly, police cracked down on nationwide protests and responded with unlawful use of force, mass arbitrary arrests and suppression of information.

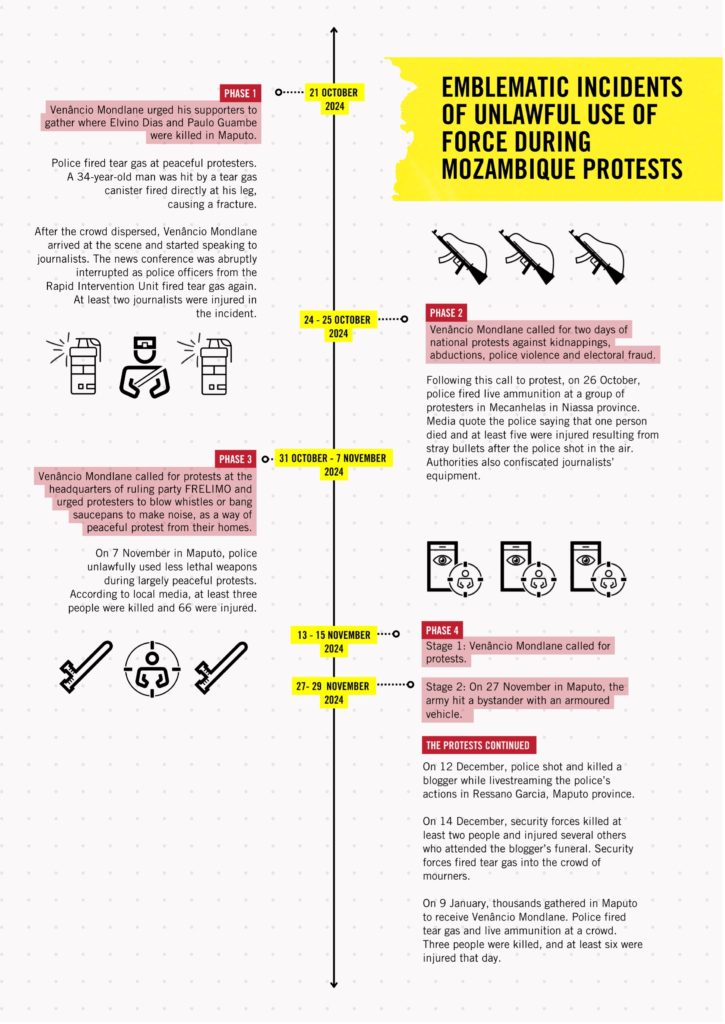

On 9 October 2024, Mozambicans voted to elect a new president, new national assembly members and new members of the ten provincial assemblies. Following the announcement by the National Electoral Commission that Daniel Chapo, the candidate for the Mozambique Liberation Front, better known as FRELIMO, had won the election, opposition leader Venâncio Mondlane contested the election results and called for a nation-wide labour strike. In the following days, thousands across the country took to the streets to protest, singing and chanting slogans of change. Despite isolated incidents of violence by some protestors the demonstrations were largely peaceful.

This report examines human rights violations by units of the Mozambican security forces, in relation to the protests between 21 October 2024 and 24 January 2025, as well as possible actions of internet service providers which resulted in impeded access to information during that time. This report documents certain emblematic cases during which authorities committed human rights violations but does not aim to be exhaustive.

The report is primarily based on interviews and open-source analysis. Amnesty International interviewed 28 people, of whom two were children, including eyewitnesses, victims, and victims’ relatives, as well as doctors and lawyers with first-hand experience responding to, respectively, those injured and arrested. Amnesty International verified and analysed over 100 videos and photos posted on social media or shared directly with researchers. The organization also reviewed official documents, social media posts, media sources, medical documents, and publications from other civil society organizations. Amnesty International analysed data collected by internet monitoring organizations and through Open Observatory of Network Interference Probe tests run by persons in Mozambique. OONI Probe is an open-source app that measures forms of network interference, including internet censorship.

Amnesty International found that the Mozambican security forces used force against peaceful protesters that was reckless and unnecessary, making it unlawful. In violation of international norms and standards, the police unlawfully used firearms and less lethal weapons, killing and injuring protesters and bystanders. The army also used force and less lethal weapons recklessly and unlawfully. In the documented incidents where people lost their lives, the unlawful use of force violated the right to life of protesters and bystanders, as well as their right to peaceful assembly. In other incidents, it inflicted bodily harm. It violated the right to peaceful assembly in all incidents.

According to Plataforma DECIDE, a civil society organization that collected reports through their telephone hotline, around 315 people were killed and over 3,000 injured between 21 October 2024 and 16 January 2025 in relation to the protests.

The Mozambican police carried out mass arrests of protesters and bystanders, including children as young as 14 years old, and detained them in police stations across the country. Plataforma DECIDE reported that, between 21 October 2024 and 16 January 2025, over 4000 people were arrested and detained in the context of the protests. According to lawyers responding to these arrests, most of these arrests were arbitrary. In violation of detainees’ fair trial rights, lawyers were denied access to their clients. Four interviewees told Amnesty International that police denied detainees access to their families as well. Amnesty International documented one case of incommunicado detention and two cases of acts thatmay constitute torture or other ill-treatment.

In Mecanhelas in Niassa province, Mozambican authorities also tried to suppress information about the protests and police response by intimidating journalists and confiscating their equipment.

In October and November 2024, the Mozambican government also seemed to have moved to limit online access to protestors. Evidence strongly suggests that internet service providers Vodacom Mozambique, Tmcel, TV Cabo and Movitel blocked or lowered access to their services at key moments during the wave of protests, including blocking users from accessing Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, which limited people’s ability to seek, receive and impart information. Amnesty International is concerned that the internet service providers did so without complying with their international human rights responsibilities, thereby possibly contributing to violations to the rights to access to information, freedom of expression, association and the right to peaceful assembly, however the companies did not respond to the organization’s request for further information. Statements by Mozambique’s National Institute of Communications and Mozambique’s then Minister of Transport and Communication, Mateus Magala, suggest that state actors ordered the internet disruptions, potentially in violation of international human rights law.

Amnesty International calls on the Mozambican authorities to ensure that all allegations of killings, bodily harm, arbitrary arrests and detention, and other human rights violations by law enforcement officials in the context of these protests are thoroughly and impartially investigated, and that those suspected to be responsible are brought to justice in fair trials. The Mozambican government must also ensure that victims are enabled to obtain prompt reparation from the state, including restitution, fair and adequate financial compensation, and appropriate medical care and rehabilitation. Amnesty International calls on Vodacom Mozambique, Tmcel, TV Cabo and Movitel to ensure that their operations, products and services, including the provision of internet services, respect human rights and to investigate and address the adverse human rights impacts that the internet disruptions and/or restrictions to social media platforms may have had.

On 18 March 2025, Amnesty International sent letters to the Minister of Interior, the General Police Commander, the Deputy Director of the State Information and Security Service, the Attorney General, the Minister of Communication and Digital Transformation, the CEO of the National Institute of Communications, and to Vodacom Mozambique, Tmcel, TV Cabo and Movitel, to share the key findings of this research and to seek their response. At the time this report was published, no response had been provided by the authorities and companies.

Methodology

This report examines human rights violations by units of the Mozambican security forces, in relation to the protests between 21 October 2024 and 24 January 2025 as well as possible actions by internet service providers which resulted in impeded access to information during that time. The geographic scope of the research covers Maputo City and Ressano Garcia village, in Maputo province, and Mecanhelas district and Lichinga city, in Niassa province. This report documents certain emblematic cases during which authorities committed human rights violations but does not aim to be exhaustive.

The report is primarily based on interviews and open-source analysis. Amnesty International interviewed 28 people, of whom two were children, including eyewitnesses, victims, and victims’ relatives, as well as doctors and lawyers with first-hand experience responding to, respectively, those injured and arrested. Amnesty International’s Digital Verification Corps and Crisis Evidence Lab verified and analysed over 100 videos and photos posted on social media or shared directly with researchers between 21 October 2024 and 15 January 2025. Amnesty International also reviewed official documents, social media posts, media sources, medical documents, and publications from other civil society organizations. Amnesty International analysed data collected by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), an internet monitoring organization, through OONI Probe tests run by persons in Mozambique. OONI Probe is an open-source app that measures forms of network interference including internet censorship.[1]

All interviews were conducted remotely, through secure communications platforms in Portuguese and translated into English, except for one which was conducted in English. All interviewees were informed of the nature and purpose of the research, how the information would be used, as well as possible consequences of the interview, and were given a choice about whether they wanted to participate. Informed consent was obtained from each interviewee. Parental consent or consent by a close relative was obtained to interview the two children. Names and other identifying details have been omitted to protect identities of interviewees for security and confidentiality reasons. In most cases, pseudonyms are used.

This report builds on Amnesty International’s past work documenting unlawful use of force by Mozambican security forces in policing public assemblies, including election-related protests in 2019, as well as civic space-related violations and war crimes and human rights violations committed in Cabo Delgado province.[2]

On 18 March 2025, Amnesty International sent letters to the Minister of Interior, outlining the report’s preliminary findings and requesting a response. Copies were sent to the General Police Commander, the Deputy Director of the State Information and Security Service (Serviço de Informações e Segurança do Estado – SISE), the Attorney General, the Minister of Communication and Digital Transformation, and the CEO of the National Institute of Communications. On 18 March 2025, Amnesty International also sent letters requesting information and requesting a response to the report’s findings to Vodacom Mozambique, Movitel, TV Cabo and Tmcel. At the time of publication, no response was received from the authorities or the companies.

background

On 9 October 2024, Mozambicans voted to elect a new president, new national assembly members and new members of the ten provincial assemblies. The elections took place amid socioeconomic and political challenges stemming from a devastating combination of an ongoing multi-year non-international armed conflict in Cabo Delgado, poverty, high cost of living, unemployment that particularly affects the youth, and restricted civic space.[3]

On 13 October, the National Electoral Commission (Comissão Nacional de Eleições – CNE) announced, while still counting the votes, that Daniel Chapo, the Mozambique Liberation Front’s (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique – FRELIMO) candidate, had won the election.[4] The preliminary results kept FRELIMO and its candidate in power, which has been consistent since the country’s independence in June 1975.[5]

In the following days, Venâncio Mondlane, an independent presidential candidate backed by the opposition Optimist Party for the Development of Mozambique (Partido Otimista pelo Desenvolvimento de Moçambique – PODEMOS), claimed electoral fraud and called for a nationwide labour strike.[6]

On 19 October, unidentified men killed Venâncio Mondlane’s lawyer, Elvino Dias, and PODEMOS spokesperson Paulo Guambe.[7] Venâncio Mondlane urged his supporters to continue with the original plan of a strike on 21 October and to gather in Maputo at the location where Elvino Dias and Paulo Guambe were killed.[8] Police broke up the peaceful demonstration and on the following day Venâncio Mondlane announced a new wave of protests lasting 25 days, saying: “Twenty five bullets hit Elvino. For 25 days we will terrorize the terrorists”.[9]

The campaigning and election period was stained by reports of arbitrary arrests and restrictions on the rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly.[10]

On 24 October, the CNE announced that Daniel Chapo had won the presidency, with Venâncio Mondlane coming in second.[11] Protesters took to the streets for two days and an internet shutdown was reported.[12] Over the following weeks, Venâncio Mondlane called on Mozambicans to express their discontent at the election results and the state of the country by non-violent actions including blowing whistles, banging pots, protesting outside CNE and FRELIMO headquarters and shutting down public transport.[13]

Thousands of Mozambicans took to the streets, fuelled by long-standing socio-economic and political grievances, protesting the election results and demanding, amongst others, better work and living conditions and an improvement to the status quo.[14]

On 23 December, the Constitutional Council confirmed Daniel Chapo the presidential election winner,[15] and on 15 January 2025 he was sworn in as president.[16] Protests have continued throughout this whole period and until the time of publication.[17]

Concerningly, on 24 February, President Daniel Chapo compared protests to terrorism as he addressed provincial authorities during his visit to Cabo Delgado province, saying: “Just as we are fighting terrorism and there are young people who are shedding their blood for the territorial integrity of Mozambique, for the sovereignty of Mozambique, to maintain our independence here in Cabo Delgado, even if we have to shed blood to defend this homeland against demonstrations, we will shed blood.”[18]

unlawful use of force

Amnesty International’s Digital Verification Corps and Crisis Evidence Lab verified 105 videos and photos that showed evidence of the use of lethal and less lethal weapons by security forces in the context of the protests. The images show, and eyewitnesses’ testimony confirm, that Protection Police officers (Polícia de Protecçao – PP), Rapid Intervention Unit (Unidade de Intervenção Rápida – UIR) officers, Traffic Police officers (Polícia de Trânsito – TP), the military as well as men in plain clothes, likely from SISE, were deployed.[19] Amnesty International identified the use of lethal weapons, such as AK-pattern rifles and handguns, as well as less-lethal weapons, such as single and multi-shot 37/38mm launchers, that fired tear gas grenades and kinetic impact projectiles (KIPs, popularly known as “rubber bullets”). In addition, several videos show that shotguns have been widely used against protesters, in some cases loaded with metal pellets, which are highly inaccurate and excessively harmful and therefore law enforcement officials should be prohibited by law from using them against persons.[20]

Two physicians who treated dozens of persons injured in the context of the protests told Amnesty International that they saw patients injured by bullets, KIPs, and tear gas.[21] Injuries included bone fractures, internal bleeding, serious damage to organs, chest injuries, and breathing problems.[22] Combined, they treated at least 10 children, of which the youngest was nine years old.[23] According to the Medical Association of Mozambique, there was a noticeable spike in the number of patients admitted to hospitals around Mozambique with bullet wounds starting on 18 October. Between 18 and 26 October, there were 73 cases of bullet wounds, of which 10 resulted in death. In contrast, there were no such cases between 1-17 October.[24]

The police’s unlawful use of force had far-reaching impact on affected persons’ physical and mental health. Two doctors told Amnesty International that some of the injuries that they treated resulted in permanent disabilities, including amputations and, in at least three cases, the loss of the ability to walk.[25]

Police’s unlawful use of force that resulted in injuring breadwinners impacted their ability to care for their families.[26] For instance, Paulo (pseudonym), a Venâncio Mondlane supporter who was injured by police gunfire in October, said: “I used to farm, agriculture. I have no means to do that, I have to be cared for, even to do farming is really difficult now.”[27] Paulo’s relative told Amnesty International that, before his injury, Paulo was the main provider for his eight children.[28]

According to Plataforma DECIDE, a civil society organization that collected reports through their telephone hotline, around 315 people were killed and over 3,000 injured between 21 October 2024 and 16 January 2025 in relation to the protests.[29]

On 23 January, Bernardino Rafael, the then police commander, acknowledged that 96 people had died during protests, including 17 officers.[30]

On 22 January 2025, President Daniel Chapo said in a media interview that his government “would work to investigate all the situation,” acknowledging citizens’ deaths as well as those of police officers.[31] On 4 February, media reported that Mozambique’s Attorney General, Américo Julião Letela, announced the opening of 651 criminal and civil cases in relation to “all situations that resulted in death, bodily harm or destruction of public or private property, resulting from violent protests” and that this process will “identify the perpetrators, determine the circumstances and other elements that allow for the [sic] effective accountability.”[32] However, at the time of writing, he has announced no further details and no information had been shared about the progress or outcome of any investigation.

On 23 March, President Daniel Chapo and Venâncio Mondlane met. According to Venâncio Mondlane, they agreed that the Mozambican state would provide those injured during the protests with free medical care, financially compensate and provide psychological assistance to families of those killed, and pardon those arrested in relation to the protests.[33]

Guidelines and standards for the use of force

The right to peaceful assembly and international standards on the use of force when policing assemblies

Under international human rights law, states have an obligation to protect, respect and fulfill the right of peaceful assembly. Law enforcement officials have an obligation not to interfere with peaceful assemblies. The police also have a duty to facilitate protests and to refrain from engaging in conduct that may lead to the arbitrary deprivation of life, such as using excessive force to police assemblies.[34]

The police also have a duty to facilitate protests and to refrain from engaging in conduct that may lead to the arbitrary deprivation of life,[35] such as using excessive force to police assemblies.[36]

The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials (Basic Principles) provide that the use of any police force shall be strictly limited to situations where it is necessary for the achievement of a legitimate law enforcement objective.[37] In cases where the use of force is unavoidable, law enforcement officials should always exercise restraint, and the level of any force used should also be strictly proportionate to the legitimate objective to be achieved.[38]

It is essential that law enforcement officials take all available precautionary measures that prevent a situation from requiring the use of force and that, when they have to use force, enable them to minimize the harm caused by the use of force.[39] In addition to respecting and protecting the right to life, police action may not result in torture or other forms of ill-treatment. Torture and other ill-treatment are absolutely prohibited under international law.[40]

As a rule, force must not be directed against peaceful protesters and the use of force for the purpose of punishment is prohibited at all times.[41] If the use of force is unavoidable, police must warn people about their intention to resort to the use of force.[42]

Authorities may only resort to the dispersal of an assembly as a last resort, and it may only be carried out when there is a pressing need and when all other means have failed to achieve a legitimate objective.[43]

Use of firearms, kinetic impact projectiles, and tear gas to police assemblies

Firearms are not a tactical tool for policing public assemblies. They may only be used when the life of an officer or the life of another is in serious and imminent danger, and there is no other less extreme measure that can effectively address the threat, and only when there is no risk of harm to other people not posing such danger.[44] Firing in the air is inherently risky and therefore constitutes an inappropriate use of a firearm in the contexts of public assemblies.[45]

Law enforcement agencies should equip their personnel with a range of less lethal weapons to respond to the various situations they may encounter.[46] Weapons may only be used in case of violence – never against peaceful protesters or against people only passively resisting any orders. The use of any weapon must be preceded by a warning and people must be given sufficient time to comply with the order.[47]

KIPs can only be used in an individualized response against persons who are involved in serious violence against other persons and pose an immediate risk of considerable injury or death, and when other methods are not an option. A warning must also be given, with sufficient time granted to comply with the order. KIPs must be aimed at the lower abdomen or legs and firing must stop as soon as the threat is resolved.[48] Each discharge must be justified on its own whether it is necessary and proportionate. They may never be fired randomly at a crowd.[49]

The use of tear gas must be strictly restricted, since it is likely to affect bystanders and peaceful protesters as well. It therefore may only be used in case of widespread violence against persons that cannot be contained by targeting only violent individuals. A warning must be given, with enough time for people to comply with the order, and people must be able to leave the area where tear gas is to be deployed. Firing teargas into confined spaces may amount to torture or other ill-treatment. Tear gas cartridges must never be fired directly at persons. Instead, if lawful to use, it should be shot over the heads of people.[50]

Police should never fire lethal or less lethal weapons from a moving vehicle, since accuracy is severely impeded.

Unlawful use of force by Mozambique law enforcement officers

In the incidents described in this chapter, the use of force by the police against peaceful protesters was reckless and unnecessary, making it unlawful. In those incidents where people lost their lives, it violated the right to life of protesters and bystanders, as well as their right to peaceful assembly. In other incidents, it inflicted bodily harm. It violated the right to peaceful assembly in all incidents.

Videos show that police officers repeatedly fired lethal weapons directly at crowds or in the air as “warning shots”, constituting unlawful use of force and inappropriate use of firearms.

Visual evidence furthermore shows that police officers also used less lethal weapons in reckless manner, typically without warning: using tear gas while there was no widespread violence and firing tear gas cartridges directly at people as well as randomly shooting KIPs at persons who did not present an imminent threat of injury to police or protestors.

On at least three occasions, videos show police officers firing their weapons from moving vehicles, which does not allow accurate shots and may constitute reckless use of force. Amnesty International identified at least two cases of severe injuries caused by tear gas canisters that were fired at body level.

Amnesty International verified one video showing police officers throwing tear gas canisters over the roofs of houses in a densely constructed neighbourhood,[51] and another video in which officers appeared to fire a tear gas canister which seemed to land on a residential balcony.[52] The use of tear gas in a confined space is an extremely dangerous practice inconsistent with international human rights standards, since people cannot easily leave the area, implying risks of panic, stampede and prolonged exposure.

Government obligation to investigate and provide reparations

The state is obliged to take effective action to combat impunity by ensuring that those suspected of criminal responsibility are investigated and prosecuted, provide victims with effective remedies including that the harm that they, and their families, endured is repaired. [53] In violation of their rights to redress, none of the victims of human rights violations or family of killed protesters or bystanders have yet received compensation. Neither has anyone been held accountable for these violations. All want justice.

Unlawful use of firearms

26 October: Six shot in Mecanhelas

Amnesty International’s Crisis Evidence Lab reviewed 20 videos filmed in Mecanhelas district, in Niassa province, on 26 October 2024, when police officials from the PP and TP fired live ammunition at a group of protesters.[54] Media quote the police saying that one person died and at least five were injured resulting from stray bullet after the police shot in the air.[56] Amnesty International was not able to independently verify the number of deaths, injuries and their causes. Three eyewitnesses told Amnesty International that PODEMOS had planned a march on that day.[57] On that same day, and in the same area, FRELIMO supporters assembled to receive the Governor of Niassa province, a FRELIMO member.[58]

One video filmed at 10:27am showed PODEMOS supporters marching in front of FRELIMO party headquarters, where FRELIMO party supporters were gathered.[59] While the video showed some PODEMOS supporters holding rocks and at least one of them throwing a rock towards FRELIMO members, the march was generally peaceful. Police officers armed with AK-pattern rifles stood between both crowds and, according to one eyewitness, managed to reduce the tension between the two groups, allowing the march to continue.[60]

Videos filmed throughout the next hour showed PODEMOS supporters setting a barricade on fire roughly 1.3km away from the first location, near a bridge.[61] Two eyewitnesses told Amnesty International that PODEMOS members started burning tyres after the police tried to stop them from marching to the FRELIMO party headquarters.[62] One eyewitness, who said he was standing close to the gathering, told Amnesty International:

“The police were trying to negotiate with the demonstrators, telling them to use a different road, but their request was not accepted by the demonstrators … The police stopped the PODEMOS members from crossing that bridge and going to the main road of the town [because FRELIMO demonstrators were coming back from this bridge and going towards the location where the Governor was going to speak]. The members of PODEMOS said we are not going to change our route, we had already scheduled this demonstration, we have shared the route with authorities. FRELIMO was not going to demonstrate. PODEMOS wanted to continue. Effectively, the police were stopping the demonstration from continuing. … That’s when they [PODEMOS members] started lighting tyres on fire and the confusion started.”[63]

A video filmed at 11:27am showed PODEMOS supporters laying tyres, sticks and large tree branches on the road near the FRELIMO gathering and setting them on fire.[64] A line of several police officers from the PP and TP, most of them armed with AK-pattern rifles, stood between the two groups.

Two videos showed the PODEMOS crowd dancing and waving flags around the fire when sounds of gunfire are first heard.[65] In another video, white smoke (likely tear gas) is seen on the road while officers fire their weapons in the air and towards protesters, who run away.[66] Three eyewitnesses said the police did not give any warnings before they started shooting or deploying tear gas.[67]

After 35 seconds of continuous shooting in the air and towards protesters, videos show police officers running in the direction where PODEMOS members retreated. At least four people appeared injured with blood on their clothes.[68]

At a press conference, a police spokesperson said that a PODEMOS sympathizer had tried to steal an officer’s weapon, “which forced shooting to the air and consequently, six people were hit by stray bullets and taken to the local health center. One, due to the severity of injuries, was declared dead.”[69] The videos analyzed by Amnesty International do not show the alleged attempt to steal a weapon, but even if this report is correct, when individual protestors commit criminal offences, rather than shooting at the assembly as a whole, police should seek to arrest those individuals. Any injuries that resulted from shooting into the air confirm the inherent risks involved in such a practice, in the context of public assemblies in particular.

In this incident, the police should have facilitated both groups and protected FRELIMO supporters from violent acts by PODEMOS supporters. Rather than stopping the PODEMOS march, the police should have sought to arrest those individuals committing criminal offences, but let the others proceed with their march, while keeping them physically separated from FRELIMO supporters.

12 and 14 December: Killings in Ressano Garcia

On 12 December 2024, 30-year-old Albino José Síbia, also known as Mano Shottas, was shot and killed while livestreaming the police’s actions in the border town of Ressano Garcia, in Moamba district, Maputo province. At the time, Albino José Síbia had more than 60,000 followers on three different profiles on Facebook, where he shared local news, music and personal interests.[70]

In the weeks leading up to Albino José Síbia’s death, protesters blocked the border crossing at Ressano Garcia, one of the main entry points connecting Mozambique with South Africa.[71] On 12 December 2024, videos showed long queues of people at the border crossing.[72] Local media reported that the police intervened to open the flow of people and trucks.[73] In that context, Albino José Síbia went out to film what was happening.

During his 51-minutes long Facebook livestream, Albino José Síbia points to white smoke coming out of a building and says that there are children in the house.[74] Then sounds of gunshots are heard. The camera turns to the right and at least three police trucks are seen parked on the road where Albino José Síbia is standing. He covers the lenses of his phone briefly and says that he cannot film anymore. An unintelligible conversation follows, then a loud noise is heard, and the camera turns black. Albino José Síbia is heard saying: “I was shot, guys. I’ve been shot. Help! Help!” He appears to talk to someone near him: “I was hit on my back. I can’t turn.” He turns the camera to himself and says: “Guys, I’ve been shot. They keep shooting.”

A video filmed from a different angle showed Albino José Síbia alone lying on the road, likely after being shot.[75] Another video showed him receiving medical attention, a towel soaked with blood on his back.[76] According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) who spoke with an eyewitness, a police officer shot Albino José Síbia twice, after he refused the police officer’s order to stop filming. CPJ reports that Albino José Síbia died four hours later while being transferred to a hospital in Moamba district, Maputo province.[77]

From the videos analysed, Albino José Síbia did not pose an imminent threat of death or serious injury to any person, rendering, as a minimum, his fatal shooting an unlawful killing and a violation of his right to life. While Amnesty International was unable to determine the intent of the police officer, the fact that Albino José Síbia was shot twice could suggest that the police officer intended to kill him. If the latter is the case, then the killing would amount to an extra-judicial execution. Extra-judicial executions, the deliberate killing of an individual by a state agent without judicial authority in line with fair trial rights, are a violation of the right to life protected by various human rights instruments including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) to which the country is a state party.[78]

The Centre for Democracy and Human Rights (Centro para Democracia e Direitos Humanos – CDD), a civil society organization, has taken the shooting of Albino José Síbia to court.[79]

On 14 December 2024, at least two people were killed, and several were injured while attending Albino José Síbia’s funeral, according to two eyewitnesses and local media.[80] Two videos show the moment when tear gas was fired at a crowd that was gathered at the cemetery where Albino José Síbia was being buried.[81] An eyewitness recounted the day:

“At the end of the burial, we started hearing gunshots. That place was crowded. …They were also firing teargas a lot.”[82]

The eyewitness said he saw members of the police, UIR, and border control all engaged in the attack.[83]

A video broadcast live on Facebook by a journalist showed police trucks parked on a road near the cemetery, one of them with a person seemingly injured in the back.[84] As the journalist films, he realizes he is being watched. “They are aiming at us!” he screams. Sounds of gunshots are heard and the cell phone with which he is filming seems to fall on the ground. Moments later, another person picks up the phone and films the journalist, who is wearing a vest identifying him as such, with blood on his hand.

According to the Media Institute of Southern Africa, 29-year-old Strip Pedrito was shot in the arm by officers of the UIR. His colleagues called an ambulance but were told that the police had blocked all roads and even ambulances were not allowed to circulate.[85]

9 January: Shot dead while waiting for Venâncio Mondlane

Three people were killed, including 33-year-old casino inspector Carlos Gabriel Guedes Mula,[86] and at least six were injured with gunshot wounds related to incidents on 9 January 2025 in Maputo.[87] That day, thousands gathered on the streets of Maputo to receive Venâncio Mondlane, who had been out of the country since October 2024. Supporters tried to march to the Mavalane Airport, where Venâncio Mondlane’s flight landed in the morning, but were stopped by the police. Videos show that police officers fired AK-pattern rifles in the air on an empty street and tear gas canisters at crowds who were blocking a street near the airport. Some protesters responded by throwing rocks back at the police.[88]

As Venâncio Mondlane’s car reached Estrela Vermelha market, some 5 kilometres away, where he was scheduled to speak, police fired tear gas and live ammunition to disperse the crowd that waited for him on the street.[89] A news crew that was following Venâncio Mondlane’s car captured the sounds of gunshots and immediately after filmed a man lying on a sidewalk with an apparent gunshot wound on his head.[90] Though the circumstances of the shooting are unclear, some individuals throwing rocks does not in and of itself justify the use of lethal force by police, and there is no additional indication of violence in the area that could justify the use of such force. An eyewitness told Amnesty International:

“Everything was still peaceful, and we were there just to receive the candidate [Venâncio Mondlane]. We were walking together, just singing “people power”. … Minutes before he was getting out of the car to give the speech, the police started to shoot. … I was in the middle of the crowd. We were very close to each other. There were a lot of people, maybe around 5000. The [UIR] police started to shoot. As the police started shooting, everybody started to run. … A young man was shot by the police. That was terrible and he died immediately.”[91]

Pedro (pseudonym), a 16-year-old student, who was waiting to hear Venâncio Mondlane speak told Amnesty International:

“The first person that was in front of me, [they] shot him in the head, and he fell down. After that, I ran away and then suddenly, the moment I was turning, they had already shot me, and I fell backwards.”[92]

Pedro said that his friends rushed him to a hospital where he underwent surgery.[93] He said the bullet entered his body close to his spine.[94] “I was lucky, otherwise I wouldn’t walk anymore,” Pedro said.[95]

Videos filmed throughout the day also showed police and men dressed in civilian clothes firing AK-pattern rifles on the streets of Maputo.[96]

Unlawful use of less lethal weapons

On 21 October 2024, protesters gathered at the location where Elvino Dias and Paulo Guambe had been killed two days earlier, on Avenida Joaquim Chissano, in Maputo. Amnesty International’s Evidence Lab verified three videos which showed a group of protesters standing on one lane of the avenue holding signs and chanting words such as “this country is ours” and “save Mozambique”, while UIR police officers and armoured vehicles blocked the road.[97] The videos show that the crowd was relatively small, not violent and did not pose an imminent threat to police officers or other individuals. One eyewitness said he saw UIR officers, PP, canine police, and National Criminal Investigation Service (Serviço Nacional de Investigação Criminal – SERNIC) officers present.[98]

21 October: Tear gas and kinetic impact projectiles fired at journalists

In a Facebook livestreamed video, a journalist said: “Nobody enters, nobody leaves,” as the camera showed the line of armed police officers from the UIR.[99] “The police have blocked everything. This side is blocked, the other one as well,” he said. Two eyewitnesses corroborated this account, one confirming it was UIR police officers and armoured vehicles.[100] “No-one could get in and no-one could get out,” they said.[101]

In the video, less than one minute later, the line of UIR police officers started walking towards the protesters and fired tear gas canisters at them.[102] It is unlawful to fire tear gas at groups of people who are peacefully protesting.

A 34-year-old man was hit by a tear gas canister fired directly at his leg, causing a fracture.[103] He told Amnesty International:

“I saw one police commander talking on the phone. As soon as I saw the commander on the phone, I felt something on my foot, and I suddenly couldn’t feel my foot anymore. There was shooting [without warning].”

One eyewitness told Amnesty International that people responded to the tear gas by throwing rocks at the police, who, in turn, started randomly firing weapons.[104]

After the crowd dispersed, Venâncio Mondlane arrived at the scene and started speaking to journalists. The news conference was abruptly interrupted as police officers from the UIR fired tear gas again.

“Tear gas is being fired at this moment at the location where journalists and also Venâncio Mondlane are,” said a journalist who was interviewing the opposition candidate live on TV.[105] “There are no conditions [to continue our work], we have to disperse,” he said in the video while a large explosion, followed by a cloud of white smoke, was seen behind him. An eyewitness who was injured on his feet, arms and lower back told Amnesty International:

“They saw me running … yet they fired teargas to my right foot and that thing exploded. I lost my senses. I remember standing there for 30 seconds without knowing who I was. When I recovered my senses, I looked at my feet and I saw that my trousers and my shoes were destroyed. I saw water coming out, but when I looked again, I saw that it was … blood. I don’t know how, but the shirt I was wearing was white. It was also full of blood.”[106]

At least two clearly identifiable journalists were injured in the incident.[107] According to Maputo’s Central Hospital, 16 people were injured throughout the day.[108]

Later on the same day, protesters set up barricades and burned tyres on Avenida Vladimir Lenine. In a video, a journalist said that police fired rubber bullets (kinetic impact projectiles).[109]

“The police don’t let us leave, they are surrounding us, where should we go?” a protester told the journalist in the video.[110] The interview was abruptly interrupted by sounds of gunshots and the crowd dispersed.

“We are trying to escape. The police are shooting,” said the journalist. “Rubber bullets are being fired here.”[111]

Two videos verified by Amnesty International show the moment when an unidentified less lethal projectile was fired from a moving armoured vehicle, hitting a passerby in the head.[112]

After the firing, in disrespect of international human rights standards,[113] police also failed to stop, check for any injuries they may have caused and eventually provide medical assistance. Instead, other passersby wrapped a T-shirt around the person’s bleeding head and carried him away.

7 November: Tear gas fired at kneeling protesters

At least three people were killed and 66 were injured during largely peaceful protests in Maputo on 7 November 2024, according to local media.[114] Visual evidence verified by Amnesty International showed misuse of less lethal weapons, such as police firing tear gas canisters in an uncontrolled manner, from a moving vehicle and directly at protesters, including at a group who were kneeling with their hands up.[115]

Two videos filmed in Maputo’s Alto Mae residential neighbourhood showed men in plain clothes with their faces covered firing AK-pattern weapons. A uniformed police officer was filmed walking alongside one of them.[116]

Another video showed protesters carrying an injured person in the same area.[117] An eyewitness described the situation:

“After I woke up, I started feeling sick because of the [tear] gas. There was a lot of [tear] gas inside my apartment. [My friends and I] decided to go to the rooftop because there the gas wouldn’t reach us. We had to go upstairs with damp cloths on our noses so we could breathe. After a few minutes, we saw the demonstrators coming. They were mostly young and they were carrying flags from the [PODEMOS] party and flags with a picture of Venâncio Mondlane. They were chanting “people and the power, the country is ours.”

The eyewitness said they saw security forces arrive and start shooting tear gas and lethal ammunition. Amnesty International was unable to confirm the exact units of the security forces and whether lethal ammunition was indeed fired. The eyewitness continued:

That’s when the protesters started running away… Me and my friends saw the man bleeding and some of his friends and some of the other protesters tried to carry him away. At one point, we saw a young man walking on the street. The police started chasing him. Me and my friend started throwing rocks at the police. … We believed that, if officer had gotten him, he would have been arrested, or something would have happened to him…. The police threw tear gas to the rooftop where we were standing.”[118]

27 November: Unnecessary use of force by the Army

As a general rule, military armed forces should not be involved in the policing of protests and must only be used in exceptional circumstances and only if absolutely necessary.[119] However, as the demonstrations continued, the Mozambican army was deployed, which led to additional unlawful uses of forces against protestors. On 27 November 2024, videos verified by Amnesty International show a Dongfeng Mengshi, a large, armoured vehicle designed to move infantry in combat, speeding down Eduardo Mondlane Avenue, where peaceful protesters gathered holding signs, chanting slogans and honking horns.[120] One of the people filming the scene with her cell phone was Maria Madalena Matusse. As the armoured vehicle approached a sign with Venâncio Mondlane’s picture, protesters in the area immediately ran away. Maria Madalena Matusse stood behind the sign, in an apparent attempt to let the remaining vehicles of the column pass before crossing the street. Eight other people stood around the sign, four of whom would have been visible to the persons inside the armoured vehicle. They managed to get out of the vehicle’s way just in time. The armoured vehicle did not attempt to avoid them or slow down and instead, at high speed, and without being able to see whether anyone was still behind the picture, ran over Venâncio Mondlane’s picture, hitting Maria Madalena Matusse to the ground, who could not see the vehicle. Despite the heavy contact, the military vehicle continued its route, leaving Maria Madalena Matusse’s motionless body lying on the tarmac. Protesters took Maria Madalena Matusse to the hospital.[121] Miraculously, Maria Madalena Matusse survived. Reckless disregard for the lives of protestors and extreme careless negligence in the use of force by state security personnel is unlawful.

Less than 100 meters from the location where Maria Madalena Matusse was hit, security forces in a moving CASSPIR Mine Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicle fired a shotgun and struck a man in the head and upper body, as can be seen on one video verified by Amnesty International.[122] Immediately after being shot, the man brings his hands to his right eye, while blood stains appear on his white T-shirt. Videos also showed the injured man running to a hospital nearby.[123] Pictures published days later showed injuries on the man’s face and shoulder consistent with the use of “birdshot”, or small metal pellets that are used in shotguns.[124] It is never appropriate to fire birdshot at persons during policing actions.

On 27 November 2024, media quoted a statement by the Ministry of National Defence regarding the running over of a young woman with an armoured vehicle by the Mozambican Armed Forces (Forças Armadas de Defesa de Moçambique- FADM) in Maputo City that morning.[125] The video described in the media article matches the video that Amnesty International verified.

The young woman referenced in the media article is Maria Madalena Matusse. The statement is reported to claim that the “vehicle was on a mission to protect essential economic objects, clean and unblock traffic lanes, as part of the post-election demonstrations and was part of a duly signaled military column,”[126] and that the FADM regretted the incident, assumed full responsibility for the medical and psychosocial assistance of the victim. Amnesty International confirmed that the FADM paid Maria Madalena Matusse’s hospital bills.[127] She has, however, as of mid-February, received no compensation.[128]

arbitrary arrests and detention

Civil society group Plataforma DECIDE reported that, between 21 October 2024 and 16 January 2025, over 4000 people were arrested and detained in the context of the protests.[129] Plataforma DECIDE reported that the overwhelming majority of the detainees have been released following intervention by lawyers.[130] Similarly, two lawyers told Amnesty International that, in response to the protests, the police–including the UIR, PP, and the SERNIC–carried out mass arrests of protesters and bystanders, including children as young as 14 years old, and detained them in police stations across the country.[131] Whilst, according to the lawyers, some of these arrests and detentions were lawful and protesters were charged with crimes, including assault and destruction of property, most were arbitrary.[132] The lawyers, who had firsthand experience responding to dozens, if not hundreds, of arrests, told Amnesty International that most persons were arrested without suspicion of committing crimes.[133]

Both lawyers told Amnesty International that they had responded to the arrest and illegal detention of children around 16 years old and younger, and that these children were held in the same cell as adults.[139] One victim of arbitrary detention confirmed the presence of three children in the cell where he was held.[140] He said that the children told him that two of them had been arrested in relation to the protests.[141]

Two lawyers told Amnesty International that they were denied access to their clients and one detainee said he was not given access to a lawyer.[142] Two lawyers, a former detainee and a detainee’s relative told Amnesty International that police denied detainees access to their families.[143]

For instance, Manuel (pseudonym) told Amnesty International that on 12 January 2025 he saw a news item on the television reporting on arrests in Marracuene in Maputo Province, an area where his father, a Venâncio Mondlane supporter, was that morning. His father did not come home. Manuel said: “We were very worried that day and could not even sleep. … We went to all the police stations, crying.”[144] After almost two weeks of looking, on 24 January 2025, Manuel found his father detained at the 8th police station. Manuel said he saw his father on 24 and 25 January 2025 and after that was only allowed to communicate with him through letters.[145]

António (pseudonym), a 28-year-old businessman, told Amnesty International that, in mid-November, he and a friend were driving a motorbike in Lichinga in Niassa province and gave a lift to a man holding a car tyre. They were around six kilometers from where protests were taking place around Ponto 24 and protesters had been burning car tyres. He told Amnesty International:

“When I was arrested, I wasn’t protesting. … when we were going to the city, to the place where the person who asked for the lift would be dropped, suddenly a police car appeared. The third man who asked for the lift and had the wheel, jumped out of the moto [motorbike] and dropped the wheel. Knowing the behaviour of police … we started running away from police. They chased us for something like 5 kilometres. We stopped because police started shooting [in the air]. They forced us to carry the moto and to put it inside the pick-up car, the Mahindra, and put myself and the other person under the chairs of the pick-up. We were taken to the second police station.”[146]

António said he was arrested by six police officers wearing blue uniforms. Based on this description, Amnesty International believes this to be the PP. António told Amnesty International that, upon arresting him, police officers accused him of protesting at Ponto 24. He said that on the day of his arrest, the police took him and other detainees out of their cells, forced them to hold car tyres that the police gave them as the police took photos of them. He was released after three nights and a lawyer’s intervention. [147]

António told Amnesty International that, for the three days, he was held in unsanitary conditions, describing a broken toilet in the cell and no opportunity to bathe. He said he had to sleep on the floor of the three-by-four-meter cell with nine other detainees. One lawyer told Amnesty International that detainees were held in “deplorable conditions”, describing a lack of drinking water, no proper sanitation and mosquito-ridden cells, potentially exposing detainees to waterborne diseases and diseases such as malaria. The lawyer also said that, sometimes, detainees are denied access to food or drinking water brought by their families.[148]

José (pseudonym), a 35-year-old vendor, told Amnesty International that, on 6 December 2024, between six to eight UIR police officers snatched him from the streets in Maputo, put him in the back of a van, used his T-shirt to blindfold him and started driving around town, all the while kicking and beating him, threatening to kill him and accusing him of protesting. He said his T-shirt had a few holes that allowed him to see through.[149] José said:

“They continued driving. I didn’t know where we were going. … [When we arrived at the UIR headquarters], they took me out of the car and had to help me. I couldn’t do it myself. … I could hear different voices from the voices I was hearing before. Someone said: Here is one of the protesters. I told them I am not a protester, I was [at the market] doing business. … They started beating me on my back, my buttocks, in the middle of my back and my spine.”[150]

Amnesty International saw photos of José taken on 6 and 7 December that show bruises across his back, buttocks and the back of his legs.[151]

José told Amnesty International that police officers took his phone, forced him to give them his password and asked him if he was in Venâncio Mondlane’s WhatsApp group. After what he said felt like 30 or 40 minutes, police officers put José and another man back in the van and dropped them in the outskirts of Maputo.[152] “I only had my vest and my shorts. The shirt that they had blindfolded me with was torn. I started crying at that moment”, he said.[153]

Protection against arbitrary arrest and detention, including for children, and the right to humane detention conditions

International human rights law establishes protections from arbitrary arrest and detention.[154] Solely the participation, or suspected participation, of individuals in protests does not constitute a legitimate ground for arrest and detention and renders the deprivation of liberty arbitrary.

Once arrested, all individuals, have a range of rights including to be promptly informed of the reason for arrest or detention and of any charges, to be assisted by a lawyer, to be brought promptly before a judge, and to challenge the lawfulness of their detention.[155] Detainees also have the right to receive visits from family.[156]

Every person deprived of liberty has the right to be held in conditions that are consistent with human dignity. States’ obligations to treat people in detention with humanity is further developed in several instruments.[157] Among many other rights, international law guarantees that detainees have access to adequate food and water, bedding, items for personal hygiene and to adequate conditions, including sanitation.[158]

Torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment is prohibited by key human rights instruments ratified by Mozambique including article of 7 the ICCPR, article 5 of the ACHPR and the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT).

Children receive special protections under international law. Article 37(b) of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, that Mozambique ratified on 26 April 1994 provides that any detention or imprisonment “shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate period of time.”[159] Article 37(c) and article 17.2(b) of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child provides that children should not be detained with adults unless it is in their best interest to do so.[160] By detaining children in the same cells as adults, the authorities violated these provisions.

The detentions described in this chapter are arbitrary. The individuals were detained without any reasonable suspicion of a recognizable offence and their detention violates their right to liberty and right to a fair trial protected by international human rights lawand article 59.1 of Mozambique’s constitution.[161] For the duration that Manuel’s father was detained withoutaccess to the outside world, he was held incommunicado. The unsanitary conditions, inadequate water, and lack of adequate access to toilets and other sanitation facilities described in this chapter were inhumane and may therefore constitute ill-treatment.

The repeated beating of José by police officers in the police van and at the station are acts that may constitute torture or other ill-treatment. Forcing detainees to hand over the password to their phone without reasonable suspicion of an offence – an intrusion into their private life -, and without a warrant, as happened to José, is unlawful and violates the detained person’s right to privacy protected under various international human rights instruments including article 17 of the ICCPR.[162]

The ICCPR provides victims with the right to remedy and obliges states to ensure that the competent authorities enforce this right,[163] and gives victims of unlawful arrest or detention the enforceable right to compensation.[164]

State parties to the CAT must ensure that a “victim of an act of torture obtains redress and has an enforceable right to fair and adequate compensation, including the means for as full rehabilitation as possible.”[165] On 15 January 2025, José filed a complaint against the UIR with the police.[166] In early April, he was still waiting to hear from the police about the progress of his complaint.[167]

suppression of information

Internet restrictions

Connection outages

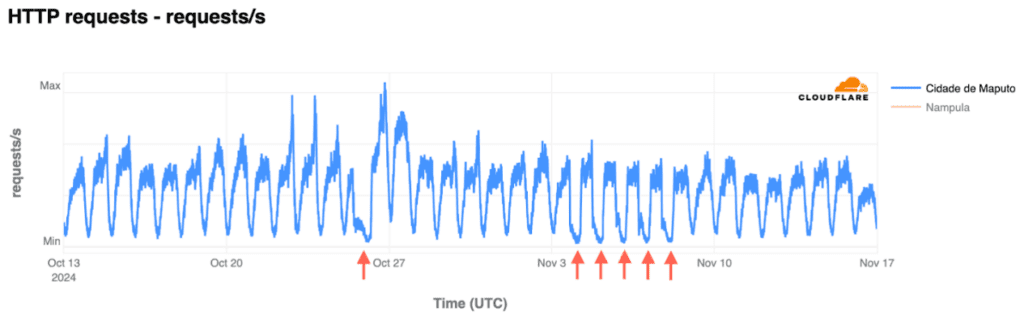

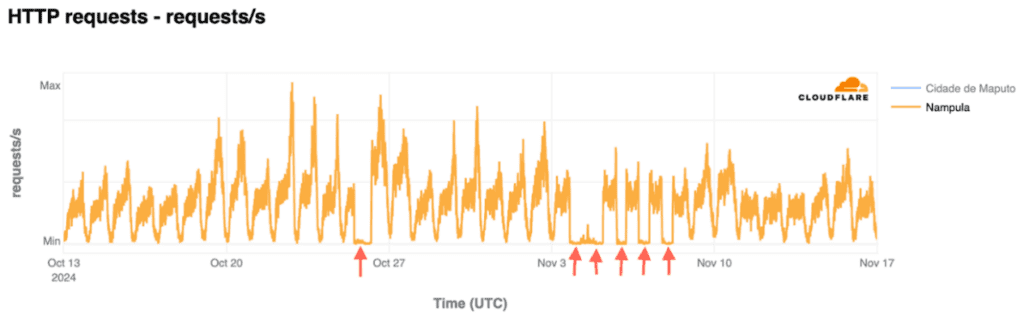

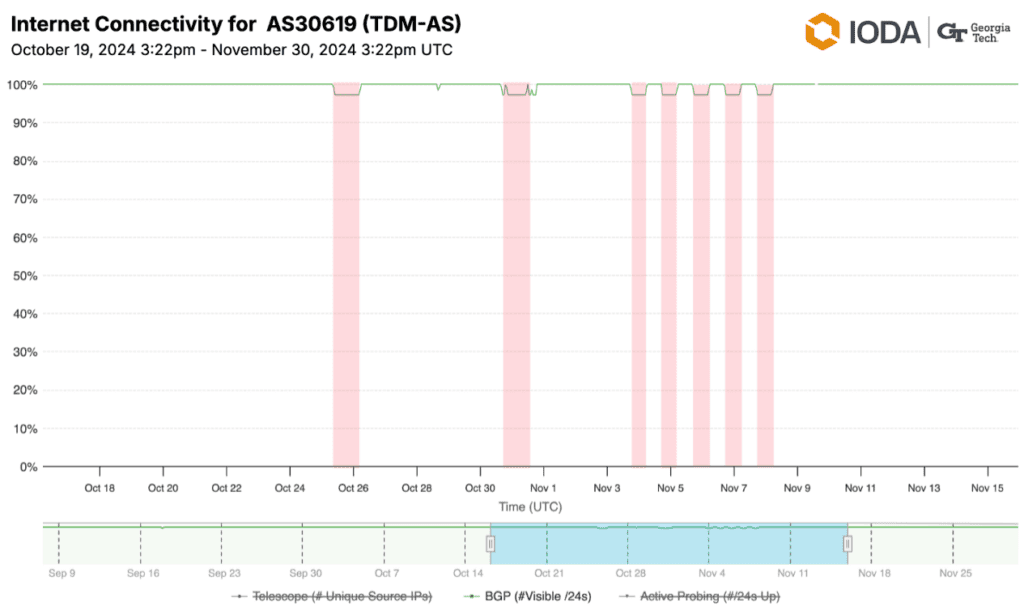

During the protests, particularly between October and November 2024, users in Mozambique reported difficulty in accessing internet and social media platforms.[168] Evidence from Internet Outage Detection & Analysis (IODA), Cloudfare Radar and Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) strongly suggests that internet service providers blocked or lowered access to their services at key moments during the wave of protests.

IODA’s data shows unusual drops in internet connectivity across the country on 20 and 21 October,[169] the start of the protests. According to the data, the internet connectivity recovered and then dropped again on 23 October (a day after opposition candidate Venâncio Mondlane called for protests) and 31 October (the start of what Venâncio Mondlane called the “third phase of protests” which were to last until 7 November),[170] without full recovery.[171] Netblocks also reported significant disruption to mobile internet traffic in Mozambique on 25 October 2024 (a day that Venâncio Mondlane had called on people to protest).[172] IODA’s data shows daily shortages from 5 to 10 November.[173] Netblocks data shows nightly “internet shutdowns” between 4 and 8 November 2024.[174] These dates coincide with the third phase of the protests. During this period, Venâncio Mondlane would broadcast announcements to his supporters via social media platforms. IODA concludes that “these outages show both political and technical signatures of shutdowns.”[175]

Cloudflare Radar, a tool that allows anyone to view internet traffic, has published data showing internet disruptions on 24 and 25 October (two protest days) and on 4 to 8 November, particularly in Maputo City and Nampula.[176] With the data available, this means that the internet disruptions were felt the most in Maputo City and Nampula.

Data gathered by IODA (see graphs below) shows that users of private internet service provider Movitel and state-owned Tmcel had the most significant drops in connectivity. The red bands in the graphics below represent loss in connectivity for users of the two providers.

IODA’s data shows that internet outages between 5 – 12 November are particularly apparent for Movitel:

IODA’s data (see below) shows that Tmcel users had no connectivity on 25, 26 and 31 October 2024 and during 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8 November.[177]

Blocked social media

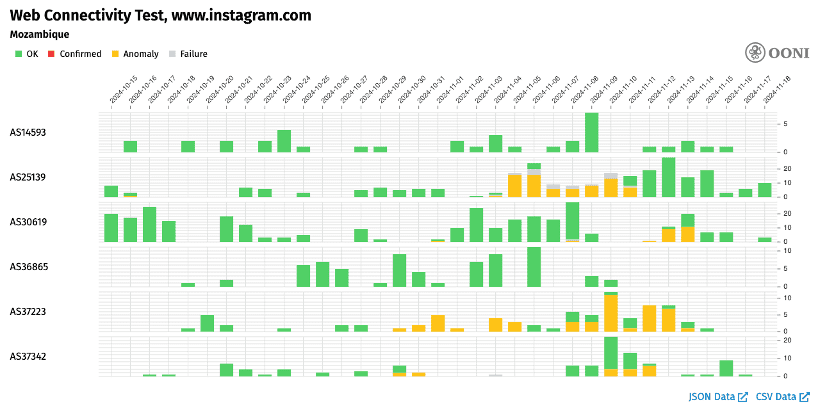

On 31 October, London-based internet monitoring organization, Netblocks, reported that live metrics showed “restrictions to social media and messaging platforms Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp in Mozambique.”[178] Data collected by the OONI strongly suggests that some internet service providers blocked users from accessing Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp.[179]

The data shows that while users of some other internet service providers were able to access the services throughout the whole period analyzed, users of Vodacom Mozambique, Movitel, Tmcel and TV Cabo could not access the same services at specific times (see graphs below). This discrepancy could suggest that the failure to connect to these social networks was not caused by a general technical issue, but due to them being blocked by Vodacom Mozambique, Movitel, Tmcel and TV Cabo.

Specifically, an analysis of OONI data (see graphs below) shows that Facebook was not accessible on Vodacom in Mozambique (AS37223) between 31 October and 13 November, Instagram was not accessible on Vodacom Mozambique (AS37223) between 30 October and 5 November and then again between 8 November and 13 November, and WhatsApp was not accessible on Vodacom (AS37223) between 30 October to 6 November and on 8 November 2024.

The OONI data suggests that Movitel (AS37342) blocked, or partially blocked, users from accessing Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp between 30 October and 12 November 2024 (see graphs below).

The OONI data (see graphs below) suggests thatTmcel (a state mobile company that resulted from the merging of telecommunication company Telecomunicações de Moçambique (AS30619) and Mcel (mobile company) limited access to Facebook and Instagram on 13 and 14 November.

The OONI data (see graphs below) suggests that TV Cabo (AS25139) limited access to Facebook and Instagram between 5 and 11 November 2024. The data also suggests that TV Cabo (AS25139) blocked WhatsApp between 4 November and 10 November 2024.

Apparent government instruction

A national media house reported that, on 31 October, Mozambique’s National Institute of Communications (Instituto Nacional de Comunicações de Moçambique – INCM), a government agency, published a statement expressing concern that telecommunications networks in the country were publishing videos and messages that “promote and encourage violent demonstrations and other acts of disobedience and social destabilization”, citing the Law on Telecommunications that provides that the use of telecommunication networks “to promote actions that are an assault against state security, and the security of people and property, constitutes fraudulent traffic, and also constitutes a threat to the preservation of national security.”[180] INCM reportedly stated that all telecommunications subscribers and operators should “collaborate with the authorities, informing them about any use of communications that contributes to the “practice of crimes that might endanger public order and tranquility.”[181] The media house reports that INCM, however, did not acknowledge ordering the internet disruptions.

A little less than two weeks later, an international media outlet reported that Mozambique’s Minister of Transport and Communication, Mateus Magala, told journalists on 10 November that there were indeed internet restrictions, justifying them by the need to prevent spreading messages and videos inciting violence during the protests.[182]

Role of the internet service providers

IODA’s, Cloudfare Radar’s and OONI’s data and analysis strongly suggests that Movitel, Vodacom Mozambique, Tmcel and TV Cabo lowered or blocked access to the internet during protests, limiting people’s ability to seek, receive and impart information. Amnesty International reviewed text messages sent by Movitel, Vodacom and Tmcel to their clients stating that “access to some social networks is temporarily restricted for reasons beyond our control.”[183]

A news site reported in November 2024 that Vodacom Mozambique, amongst others, publicly apologized for the inconvenience caused and offered users 2GB data as compensation.[184]

On 18 December, three civil society organizations filed a complaint against internet service providers for restricting internet access in the country.[185]

Legal framework on internet restrictions

Governments’ human rights responsibilities

If Mozambican authorities ordered the internet disruptions, they likely did so in violation of international human rights law. Internet disruptions can adversely affect people’s ability to exercise their rights to access to information, freedom of expression, association and the right to peaceful assembly protected by Mozambique’s constitution, and human rights treaties, including the ICCPR and the ACHPR. For example, restrictions can also negatively affect people’s ability to earn a livelihood. Internet restrictions make human rights monitoring, documenting and reporting as well as journalism more difficult.

Paragraph 10 of the United Nations Human Rights Council’s Resolution 32/13 of July 2016 “condemns unequivocally measures to intentionally prevent or disrupt access to or dissemination of information online, in violation of international human rights law.” Paragraph 34 of the General Comment 37 on the right to peaceful assembly, “prohibits blocking or hindering internet connectivity in relation to peaceful assembly.”

In 2016, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights adopted a resolution expressing concern at the “emerging practice of State Parties of interrupting or limiting access to telecommunication services such as the Internet, social media, and messaging services, increasingly during elections.”

Businesses’ human rights responsibilities

Under the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business & Human Rights (UN Guiding Principles), an internationally recognized standard, businesses have a responsibility to respect human rights wherever they operate, including throughout their operations and value chains, which includes their end users. Businesses should not infringe on the human rights of others, address adverse human rights impacts with which they are involved, and seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not caused or contributed to those impacts. As an important measure to ensure their respect for human rights, businesses are required to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for any potential negative human rights impacts resulting from their operations or as a result of their business relationships with other actors. To do so, they must engage in an early and continuous human rights due diligence process.

As circumstances change, a human rights due diligence process should be undertaken to account for these new circumstances and reassess the risks and impacts. During time of civil unrest in Mozambique, Vodacom Mozambique, Tmcel, Movitel and TV Cabo should have undertaken an assessment of how their operations and services could be impacting human rights under those new and evolving circumstances.

On 18 March, Amnesty International wrote to these companies, inquiring about their human rights due diligence policies and what processes they undertook during this period to ensure that their decisions would not lead to adverse human rights impacts. At the time of publication, no response had been provided by the companies.

In this context, Amnesty International is concerned that Vodacom Mozambique, Tmcel, Movitel, and TV Cabo may have blocked or lowered access to their internet services at key moments during the wave of protests and blocked its users from accessing social media platforms without complying with their international human rights responsibilities, thereby possibly contributing to violations to the rights of access to information, freedom of expression, association and the right to peaceful assembly.

Confiscation of equipment and intimidation of journalists

On 26 October 2024, in Mecanhelas district, Niassa province, journalists filmed the moment when police fired lethal ammunition at PODEMOS supporters, killing one person and injuring at least six people, as described in section “26 October: Six shot in Mecanhelas”.

Amnesty International verified one video showing the moment when men dressed in plain clothes approached a group of journalists who were interviewing an eyewitness of the incidents.[186] The men interrupted the interview and demanded that the journalists hand over their equipment. As one of the journalists resisted handing over the cell phone that he was using to film the scene, a man appears on camera threatening him: “I am going to beat you up! I am going to beat you up!” The cell phone then appears to be forcefully taken away.

Amnesty International spoke with two eyewitnesses who independently identified the man on camera to work for SISE in Mecanhelas district, Niassa province.[187]

Two eyewitnesses told Amnesty International that a staff member of the SERNIC was also at the scene. One eyewitness said he also saw UIR officers present.

A journalist told Amnesty International that one TP officer and one UIR officer prohibited him and a colleague from filming the protest on 7 November and threatened their lives.[188] Yet another media professional who was injured by police’s use of tear gas while covering a peaceful assembly in October in Maputo told Amnesty International that police officers visited him in the hospital, demanding he hand over his equipment and his memory card, both which he had already given to the media company that he works for.[189]

Protections against suppression of information

Under international human rights law, states are obliged to respect, protect, promote, and fulfill human rights including the right to freedom of expression, access to information and media freedom. Article 19 of the ICCPR prescribes that the right to freedom of expression includes the “freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.”[190] It acknowledges that this right carries special duties and responsibilities with it and may, therefore, “be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary: (a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others; (b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.”[191] Article 9 of the ACHPR equally protects the right to receive information and the right to express and disseminate opinions.”[192]

Independent media plays a crucial role in informing people about public affairs, government policies as well as scrutinizing government actions and reporting on human rights violations and abuses. Threatening journalists and confiscating their equipment does not meet the stringent tests enshrined in article 19.3 of the ICCPR. Instead, these actions infringe on the right to hold opinions without interference, the right to seek and receive information, and the right to impart information as protected by article 19 of the ICCPR and article 9 of the ACHPR.

recommendations

To the President of Mozambique

- Publicly condemn the use of unlawful force by security forces against protesters and develop and implement effective measures to prevent the unlawful use of lethal and less lethal force during protests, including by ensuring the establishment of robust internal and independent police oversight mechanisms;

- Ensure comprehensive reparation to victims of human rights violations and their families, including monetary compensation and medical assistance where appropriate.

To the National Police of Mozambique

- Assess whether the rules and regulations on the use of force, including less lethal and lethal weapons fully comply with the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials and the African Commission Guidelines for the Policing of Assemblies by Law Enforcement Officials in Africa and where this is not the case, review – or if lacking establish – them and duly enforce their respect in practice by all law enforcement officials;

- Ensuring that each weapon deployed in law enforcement operations is specifically regulated with clearly defined operational purposes, threshold of dangers, as well as prohibitions and precautions required in light of its design and inherent risks;

- Prohibiting the use of any weapons against peaceful protesters;

- Ensuring that firearms are not used to disperse assemblies and that they are only used in response to an imminent threat of death or serious injury and exclusively against the person posing this risk and are not indiscriminately fired at a crowd;

- Ensuring that tear gas is only used for the purpose of dispersing crowds in situations where there is widespread violence that cannot be addressed by handling violent individuals alone; they should never be used in spaces where people cannot disperse or against a peaceful assembly;

- Ensuring that KIPs are only used against individualized persons engaged in violence against another person likely to cause considerable injury to stop the violent behaviour, when other methods are not an option.

- Amnesty International recommends using its Use of force: Guidelines for implementation of the UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials and its Guidelines on the Right to Freedom of Peaceful Assembly as a reference framework;

- Refrain from arbitrarily detaining protestors, or arresting peaceful protesters who do not engage in violent behaviour that risks the security of others;

- Refrain from subjecting protesters, or individuals perceived to be protesters, to acts of torture and other ill-treatment;

- Fully cooperate with the Attorney General’s office, undertaking investigations into human rights violations committed against protesters by law enforcement officials.

To the Attorney General of Mozambique

- Ensure that all allegations of killing, bodily harm, arbitrary detention, torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment by law enforcement officials in the context of protests are thoroughly and impartially investigated, and that those suspected to be responsible are brought to justice in fair trials;

- Ensure that victims are enabled to obtain prompt reparation from the state including restitution, fair and adequate financial compensation and appropriate medical care and rehabilitation;

- Initiate a transparent and independent investigation into the internet restrictions and hold accountable those who were responsible for violating human rights.

To the Ministry of Transport and Communication and the National Institute of Communications

- Ensure that there are no internet disruptions incompatible with international human rights law and standards in the future.

To the African Union, United Nations and Bilateral Partners

- Use all bilateral, multilateral, and regional platforms at your disposal to urge the Mozambican authorities to respect, protect and facilitate the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and stop the unlawful use of force to police peaceful assemblies;

- Ensure that any bilateral law enforcement cooperation mechanisms or sales of less-lethal weaponry do not directly or indirectly contribute to human rights violations against protesters;

- Urgently review cooperation with the Mozambican government, including the provision of training, law enforcement equipment and other security assistance to Mozambican law enforcement officials, until officers responsible for unlawful use of force are thoroughly investigated and, where appropriate, brought to justice, robust accountability mechanisms are in place, and victims are enabled to obtain prompt reparation from the state including restitution, fair and adequate financial compensation and appropriate medical care and rehabilitation.

To the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights

- Urge the Mozambican authorities to implement and comply with the Commission’s Guidelines for the Policing of Assemblies by Law Enforcement Officials in Africa;

- Call on Mozambican authorities to thoroughly and impartially investigate all allegations of killing, bodily harm, arbitrary detention, torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment by law enforcement officials in the context of protests, and to ensure that those suspected to be responsible are brought to justice in fair trials;

- Consider undertaking a country visit to Mozambique to assess the extent to which authorities are respecting, protecting and facilitating the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and if access is denied, include this aspect during its review of Mozambique’s periodic state party report under Article 62 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.

To Vodacom Mozambique, Movitel, TV Cabo and Tmcel

- In line with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business & Human Rights (UN Guiding Principles), ensure that your operations, products and services, including the provision of internet services, respect human rights, including the rights to access to information, freedom of expression, association and the right to peaceful assembly, and avoid infringing on the human rights of others;

- Investigate and address the adverse human rights impacts that the internet disruptions and/or restrictions to social media platforms may have had and seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to your operations, products or services by your business relationships, even if they have not directly contributed to those impacts.

Footnotes

[1] Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), “User Guide: OONI Probe Desktop App”, 25 October 2022, https://ooni.org/support/ooni-probe-desktop/